In this guest post, Nathan Lippi, Head of User Research at PandaDoc, shares a Pareto principle approach to getting the most from a B2B Net Promoter Score program.

NPS. It’s debated, loved, and hated, but in the world of B2B SaaS it’s rarely used to its full potential.

At PandaDoc, we’ve become increasingly customer-obsessed since the introduction of our NPS program two years ago, but we feel as if we still have meaningful room for improvement.

We’ve found there isn’t much written about NPS, specifically for B2B companies, so in order to level up, we’ve gone straight to the experts. With their permission, we’re sharing some key findings here.

We hope this guide helps you to get the most out of your CX program.

Let’s get to it!

The main purpose of NPS is to drive action

NPS is an easy, trusted, and benchmark-able way to start driving customer-focused action at your company.

Many companies obsess too much about the number when they’re starting out.

However, the most successful companies never lose sight of the fact that the primary purpose of customer experience metrics is to drive customer-focused action.

Once you’re driving customer-focused action, you’ll start to actually reap the benefits of increased retention, expansion, and word of mouth.

One Oracle VP’s Three-Step Recipe for NPS Survey Success

Joshua Rossman is an NPS OG, having run NPS at eBay and McAfee, among other companies. He’s now Vice President, Customer Experience Strategy at Oracle.

Through his years of experience, Rossman has created a three-step system he uses to get the most out of customer experience surveys, including NPS. He’s been kind enough to give us permission to share it publicly.

Step 1: Ask an easy-to-answer anchor question first to improve response rates

This principle is standard for NPS, but powerful enough to use across other CX surveys.

Ask your broad question first, and get a quantitative rating. Making your first question easy to answer will improve your overall survey response rates.

Step 2: Get S-P-E-C-I-F-I-C with your open-ended ask

Rossman has found that the standard open-ended question, “Care to tell us why?” often leads to vague, inactionable responses (e.g. “It’s hard to use”).

He’s found that asking promoters for specific reasons they recommend — and non-promoters for specific ways to improve — leads to much more actionable feedback.

Here are the specific questions he recommends for brand-level NPS:

Promoters: “What is it that makes you most likely to recommend {{company}}?”

Non-promoters: “What is it we could do that would make you more likely to recommend us in the future?”

These questions ask more specific questions — and tend to get more specific answers.

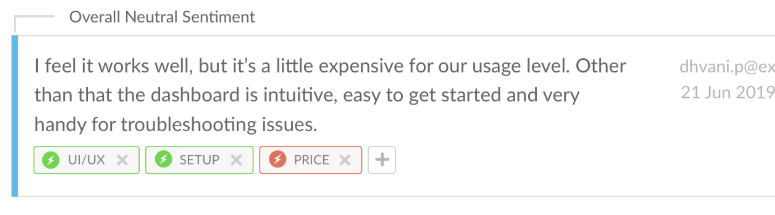

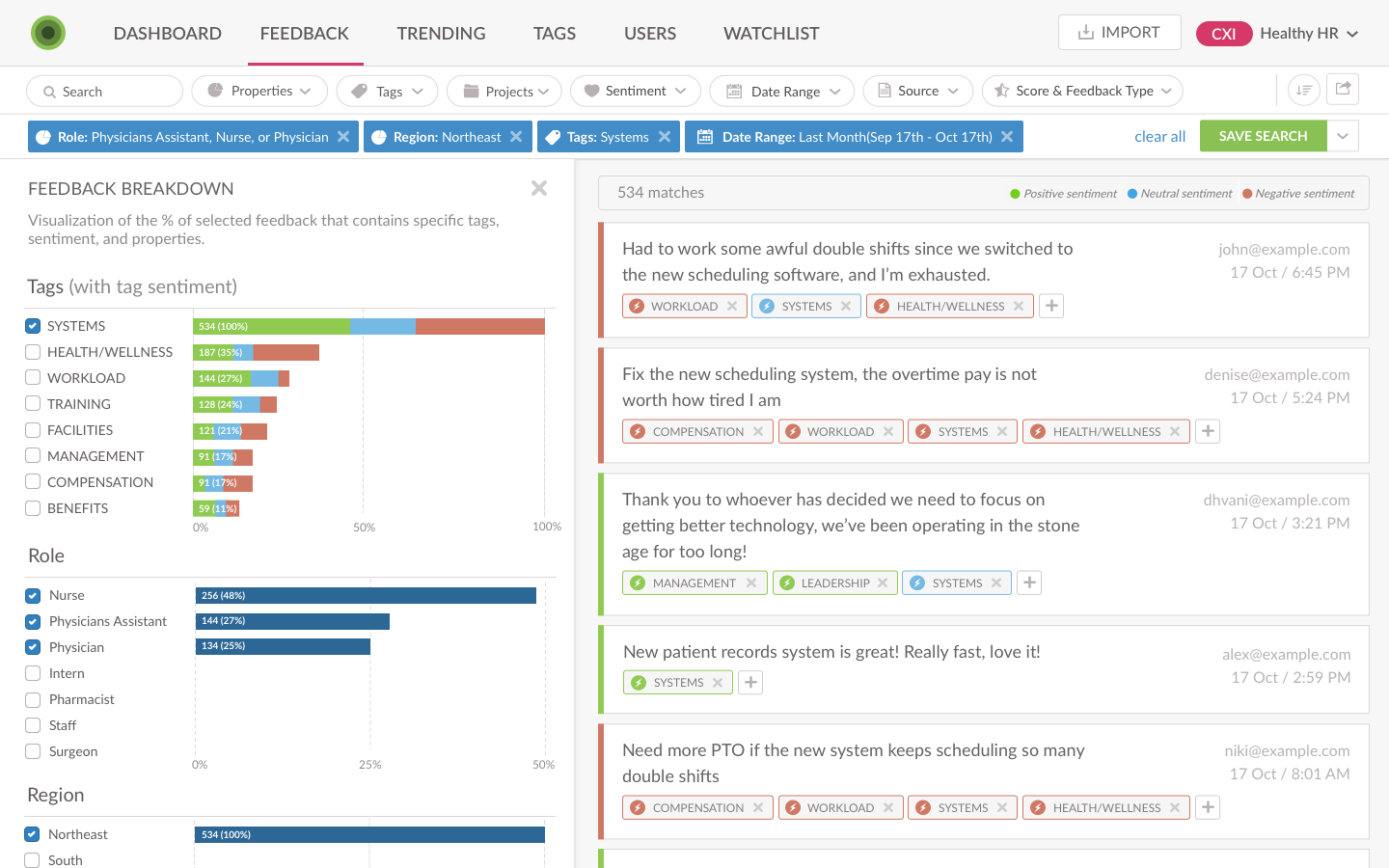

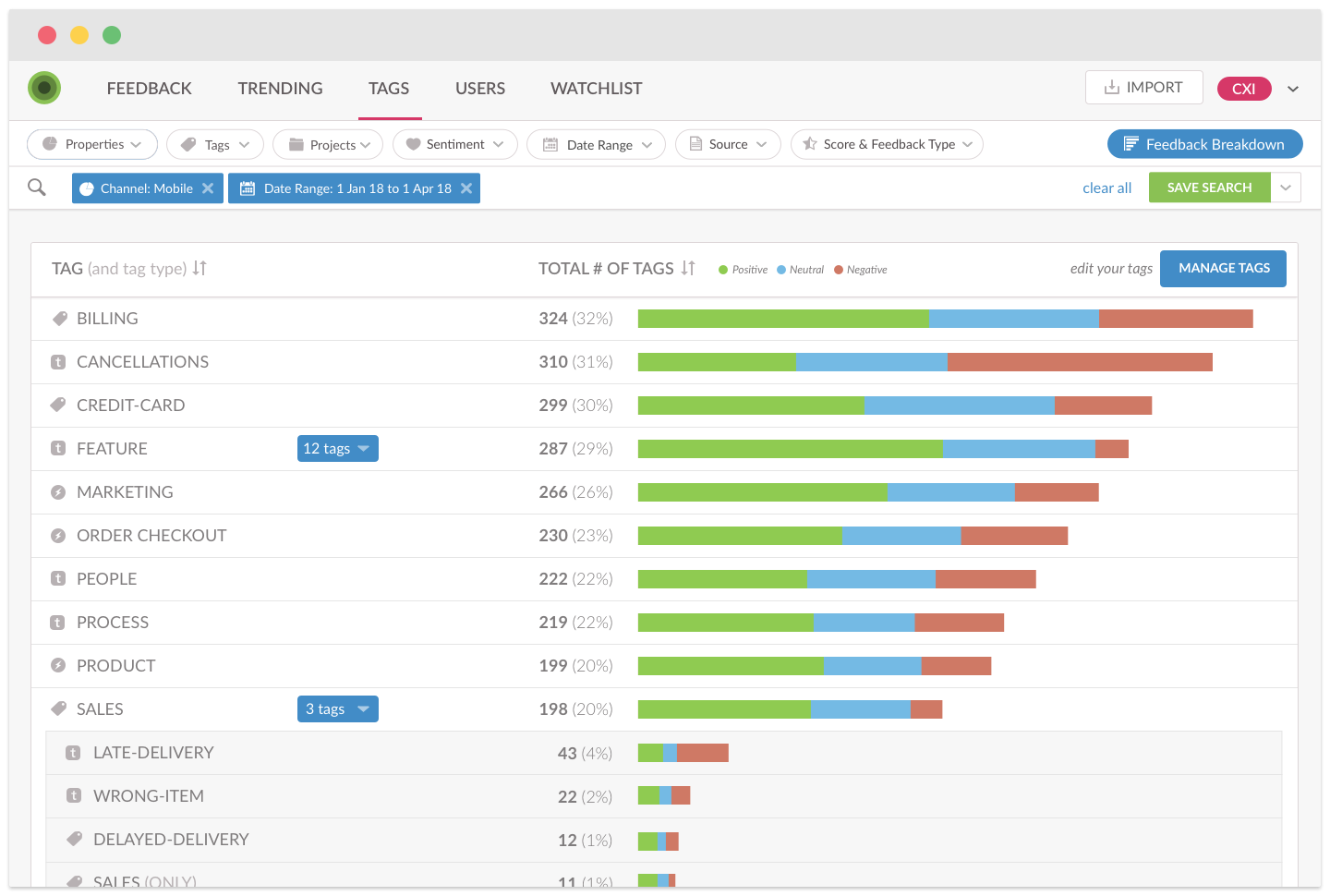

Various platforms such as InMoment can help you automatically categorize your now-more-specific NPS verbatims!

Each company will want to tag their work in a way that makes the most sense to them, but Shaun Clowes, former Head of Growth at Atlassian, says that they used machine learning to tag their feedback into three categories: Reliability, Usability, and Functionality. They used the ratio of different complaints to understand, at a high level, where their product needed work.

Step 3: NPS’ Secret Third Question

Even with the more specific responses, you’ll hopefully get from the tweaks recommended in Step 2, not all B2B companies get such a high volume of responses that they can glean mathematically reliable responses from text alone.

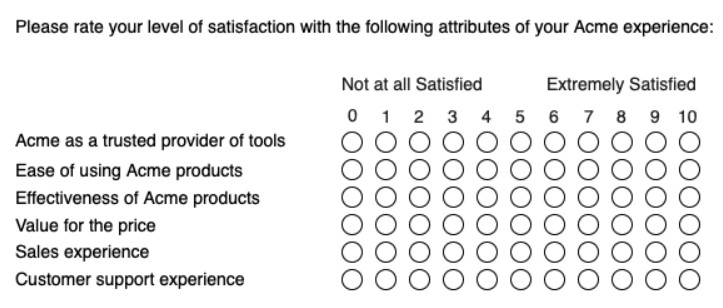

One way to gain a deeper understanding of the factors that lead to an excellent (or poor) user experience is to follow questions about satisfaction with questions about various attributes of your brand. Ask a few extra questions with NPS and you can capture the overall sentiment for each area:

After you’ve captured these details you can then run a simple linear regression, which will tell you which factors most influence if a person is a promoter or a detractor.

Various versions of the linear regression technique were also mentioned by Allison Dickin, VP of User Research at UserLeap, and other experts. Hearing them reinforce the power of this third question helps us get really excited about what we might do with it.

“Extra questions should be used judiciously,” counters Jessica Pfeifer, Chief Customer Officer at Wootric. “Think about it: When was the last time you responded thoughtfully to a multi-question survey?”

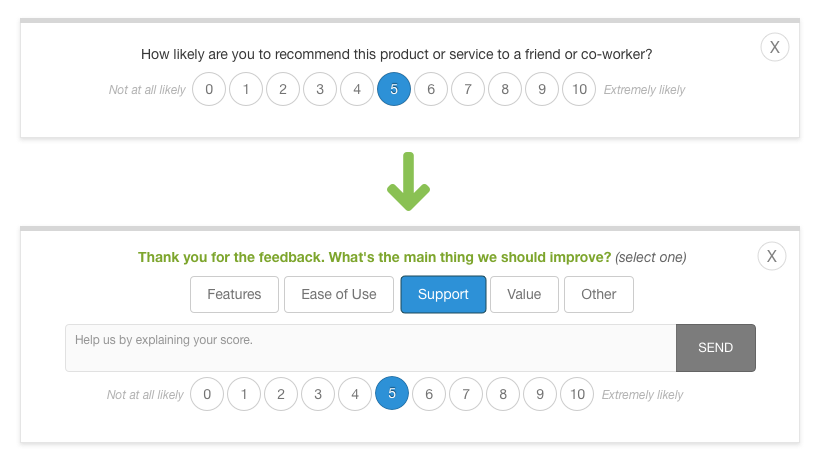

If you’re worried that such a long third step may lead to a negative user experience or lower response rates, a lighter option may be to ask the respondent to tell you what drove their score by selecting from a pick list of reasons.

If your follow-up question to detractors is, “What is the main thing we need to improve?” you could offer a picklist that includes product, support, training, and value.

Not only are you learning what’s driving your score overall, but you’re also generating groups of users to follow up based on their interests. For example, your customer support team can learn more by reaching out to detractors who cite “support” as an issue.

Drive Strategic Action with a Cross-Functional Cadence

You may have noticed that our first heading was about driving action on behalf of the customer.

We’re touching on it again because, ultimately, driving action on behalf of your customers should be the primary concern of an NPS program.

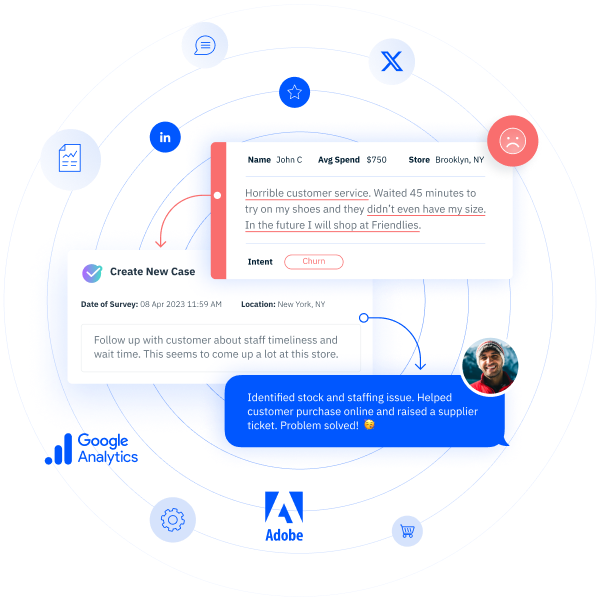

Driving tactical action on behalf of customers was something we were already doing well at PandaDoc, before talking to the experts. Getting NPS data into Slack and other systems has been a pillar of our NPS program — this helps us take immediate action on issues that surface in feedback. One example: reaching out to an unhappy detractor and quickly fixing the issue that her NPS feedback brought to our attention.

However, learning how many companies drive strategic action on behalf of the customer in the following way, was eye-opening:

- Collect customer feedback in a central repository (NPS, sales feedback, CS feedback, etc. — all combined together, somewhere like InMoment, UserVoice, or ProductBoard.

- Perform a 360° analysis of this data on a quarterly basis

- Set up a monthly cross-functional cadence to decide which action to drive, and to track progress and accountability on ongoing courses of action

Fictional Examples of Driving Strategic Action:

Product Team

Diagnosis: Self-serve onboarding is our most common NPS complaint. People often come away without understanding our platform’s core concepts.

Initiative: Improve self-serve onboarding to teach core concepts of the platform.

Success Team

Diagnosis: Feedback about CS indicates all roles except admins are quite happy. Admins specifically have trouble understanding how to set user permissions, and they’d rather avoid going through training to learn something so small.

Initiative: Create micro-videos that explain to admins on how to manage user permissions.

Support Team

Diagnosis: NPS feedback indicates enterprise customers are unhappy with the time it takes to resolve support interactions involving custom features.

Initiative: Route tickets from enterprise customers directly to senior agents who have the expertise and product knowledge to resolve their issues.

Marketing

Diagnosis: Many of the leads we’re attracting cannot benefit from our core value proposition.

Initiative: Better align their SEM campaigns and landing pages with promises that the product can fulfill.

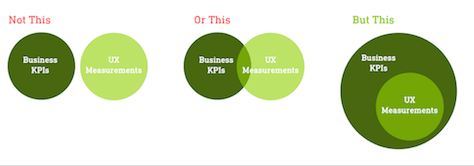

Your metrics should flow from your unique business strategy

NPS has been sold by some as the be-all / end-all metric of a customer-centricity program. But this approach can be harmful.

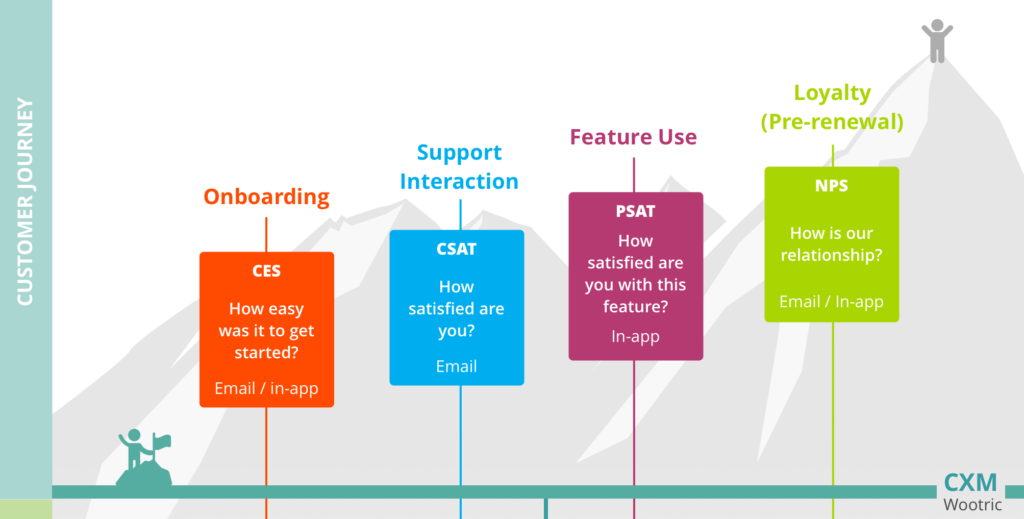

While NPS is often a great way to understand brand-level sentiment, it makes sense to layer on additional metrics as your CX program progresses.

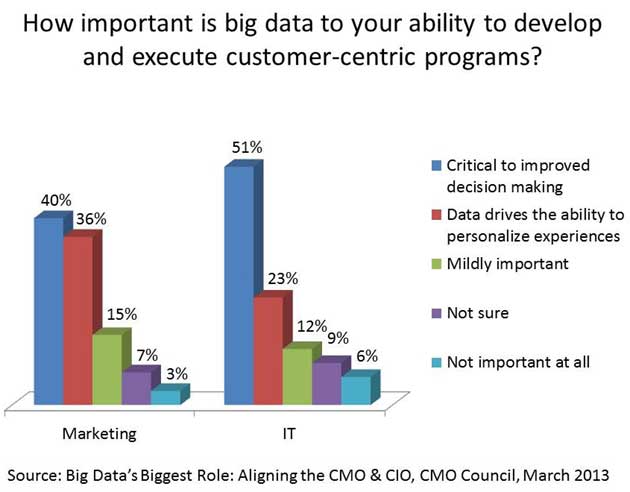

Jessica Pfeifer at Wootric and Allison Dickin at UserLeap agree on the idea that your CX metrics should flow from what’s most critical to your business’ success.

“You’ll be able to benchmark and track trends over time when you complement NPS with established customer experience metrics like CSAT, PSAT, or Customer Effort Score at critical touchpoints in the customer journey,” says Pfeifer.

“For example, you might trigger a Customer Effort Score survey to gauge how easy it is for a user to achieve ‘first value.’ What is that critical milestone in your product? In PandaDoc’s case, it might be sending a document. Here at Wootric, it’s when a customer has live survey feedback flowing into their dashboard.”

Both took time to talk to us about questions that can be used in addition to (or as an alternative to) NPS. Here are some examples:

Example Non-NPS Questions

| Business question | How to ask it | |

| Examples from Allison Dickin @ UserLeap | ||

| What are the factors that affect churn, and what can we do differently to reduce it? | First question:How likely are you to use {{company}} for the next 3 months? Follow-up question: What would make you more likely to continue using {{company}}? |

|

| How well are we delivering on our core value proposition? | First question:How well does {{company}} meet your needs for {{value prop}}?

Second question: How could {{company}} better meet your needs? |

|

| How is our first session going for users, and how can we improve it? One option here is to pop up a question in-app, before the median session time. Another option is to email users after their first session. |

First question:How would you rate your experience getting started with {{company}}?

Second question: How could {{company}} better meet your needs? |

|

| Examples from Jessica Pfiefer @ Wootric | ||

| How satisfied are users with our product, a feature, or service and how can we improve them? E.g. support interactions. Survey in product for feedback on features, survey via email or Intercom Messenger for support interactions. | CSATFirst question: “How satisfied are you with your recent support interaction? Second question (customize based on score): |

|

| We have a key but difficult task that we need to make easier for users. How difficult is the task, and how can we make it easier to do? |

CESFirst question: “How easy was it for you to {{key but difficult task}}? Second question: |

|

Takeaways

- NPS is a great way to get started with driving customer-centric action

- Use Josh Rossman’s three-part system to get the most out of your CX surveys, including NPS

- Use analysis and a cross-functional cadence to drive org-wide, customer-focused action

- As your business grows, layer on metrics that fit your specific business needs

This is just the tip of the iceberg for NPS, but we hope it will help your company squeeze the most out of your CX research program.

Hit me up on Twitter (@nathanlippi), and to let me know what’s worked well for you and your company!

Retain more customers with InMoment, the #1 Net Promoter Score platform for SaaS.